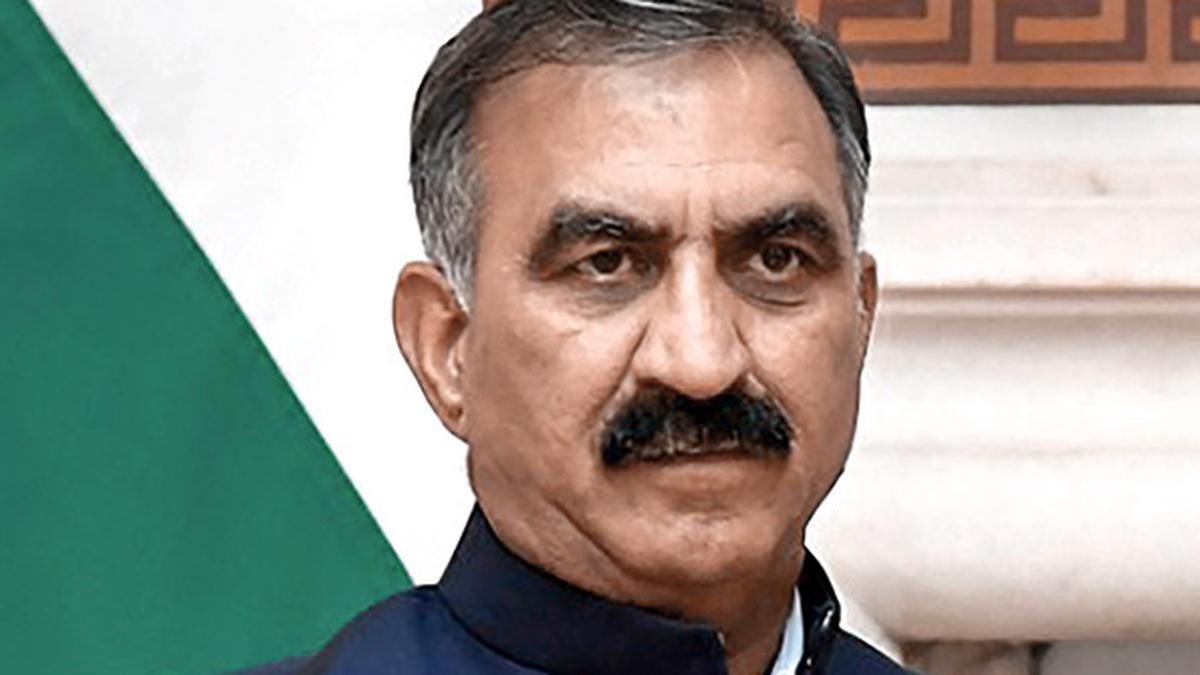

In contemporary politics, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is an enigma. He distinguishes himself from his contemporaries through his nuanced allure, eliciting varying degrees of resonance among individuals. Contrary to the conventional perception of authoritarian populist leaders, depicting forceful language, profanity, self-made narratives, and anti-elite sentiments, Narendra Modi has skilfully cultivated a succession of unique political personas. Every one of these personae represents a distinct register, conveying specific values and ideas about his leadership.

During the 2014 campaign, Modi took on the position of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Gujarat Model and presented himself as the embodiment of development, the ‘vikas purush’. He was portrayed as the offspring of a tea merchant and a self-made statesman who would usher in economic advancement and plenty to the nation. As a technological maverick, he appeared as a hologram and on social media, advocating for business collaboration to boost employment and economic progress. In the 2019 edition of the national campaign, he assumed the role of the gatekeeper, ‘chowkidar’, symbolizing the powerful guardian of India.

His supporters and the BJP campaign lauded him as a resolute leader accountable for safeguarding the nation’s borders. He exemplified the characteristics of a resilient and bold leader who could be relied upon to handle concerns of national security. As the third national election in 2024 approaches, one notable characteristic of Modi's campaign image has been that of a ‘sage king’, also known as the ‘Hindu hriday samrat’ by his political adversaries, which represents his position as a Hindu nationalist leader. He is renowned for supervising the building of the Ayodhya temple, designating a site on the moon for the Hindu god Shiva, and vigorously addressing what many see as 500 years of injustice to revive Hindu pride in the country. He exhibits strength, decisiveness, and relentlessness in all of his political roles.

In a few episodes, he gives a name to this role. He talks of himself explicitly as a chief servant or ‘pradhan sevak’ of the common people, or as more recently in his latest interview that of a ‘village-head’. He emphasises that the well-being of all Indians is at the heart of his political life, that he has no personal ambition, and claims that he never gave it a thought to rise in politics and be powerful; that his only dream was always to serve Mother India and the 125 crore Indians – a trait often associated with that of Mahatma Gandhi in the collective imagination of the people. However, all these personae of Narendra Modi, we argue, are quite distinct from each other, and yet, coexist at the same time.

Understanding ‘Modi Populism’

Political communication plays a crucial role in shaping public perceptions of leaders and their policies, and the increased role of social media plays an important role in this regard. Leaders engage in strategic communication to influence public perception, and that such political branding does influence public opinion by shaping the emotional connection between leaders and citizens. Successful branding can lead to increased trust, loyalty, and positive evaluations from the public, although the contextual factors can significantly influence the effectiveness of political communication and branding.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a party projects itself through the image of its leader, who personifies the party’s ideology, policies and programme. In contemporary India, major political parties employ public relations consultants to help adjust the figure of the leader to tailor the political message in what Julia Paley has called ‘marketing of democracy’. By combining seemingly unbiased news coverage with the uncritical dissemination of unsubstantiated stories, Indian media corporations often contribute to the fabrication of political myths.

The issue we address in this write-up, which in itself is part of our larger collaborative research project, is how to understand Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s centrality to the Hindu nationalist political project, his popularity, in other words. We are interested in the ideas and values Modi and his team of highly professional media people communicate. While doing so, we examine the official transcripts of the initial 102 episodes of Mann ki Baat, which were aired from October 2014 to June 2023. The broadcasts provide excellent material for understanding Modi’s communication strategy. While it is plausible that Modi personally scripts these monologues due to his exceptional communication skills, it is arguably likely that these shows are put together by a team of communication advisors and form part of a very consciously crafted communication strategy for a political movement that aims to sustain itself in power for a long time.

Modi’s Fourth Avatar vis-a-vis Mann ki Baat

Mann ki Baat is a monthly radio broadcast on the national All India Radio. The broadcast consists almost entirely of Modi speaking. Each episode spans about 30-40 minutes and covers 4-7 topics (or segments, as we call them). Although originally only on the radio, the broadcast was later made available on platforms such as YouTube, the NarendraModi (or NaMo) application, and the MyGov.in website. The first show was aired in October 2014, a few months after Modi became prime minister, and had by 2023 crossed 100 episodes.

Although hosting talk shows on radio or television by political leaders is not entirely a new phenomenon even in India, Mann ki Baat is extraordinary for several reasons. No other political leader in India has communicated with voters in this direct way and with such regularity and consistency. The programme also has an impressive reach. One survey claimed that more than 230 million people listened to it regularly and 410 million were occasional listeners; while another suggests much lower figures and that while 21 percent had listened to the broadcast once or twice, more than 62 percent never did. But even counting only those who had listened to the programme ‘most months’ (10 percent) or ‘some months’ (a further 7 percent), the reach is significant.

In his political campaign speeches, Modi is known to be acerbic, sarcastic, critical, and self-righteous. He ridicules opponents in his booming voice, mocking them with nick-names, accusing them of all things proven to be detrimental to the nation. However, in Mann ki Baat his political persona is fundamentally different. He presents himself as someone very different from the consummate politician he otherwise is. He avoids bad-mouthing his political opponents, criticism, and controversies of all kinds, portraying himself as a leader who only seeks the betterment of the entirety of the entire society. He is understanding, sympathetic, and inclusive, talking about how they should all work together to help improve life for everyone.

What and how does then Modi talk about in Mann ki Baat? One of the most dominant themes that comes up in his addresses is the duties and moral responsibilities of the citizens towards the nation. Modi advocates for individuals to actively engage in particular governmental endeavours and to assume personal responsibility in advancing philanthropic endeavours. He consistently promotes the idea of popular participation and asserts that government programmes should evolve into collective endeavours.

On several occasions, Modi underlines that service to the nation is a moral obligation for every citizen. His request for everyone to make a sacrifice for the greater good of the nation underlines that an essential component of his speeches is that he views duty as a responsibility towards the public rather than the government. There is an element of almost neo-liberal thinking in Modi’s insistence on the citizen’s duty and responsibility. Throughout the broadcasts, the state is virtually absent. There is only the Prime Minister and the citizen, and he is presented as someone who designs policies and guides the populace, while it is for the populace to ensure that his policies come to fruition. The implicit claim is that he has provided the way forward for India and now it is for the people to ensure success.

In order to attain this success, India’s collective development goal, ‘Viksit Bharat’, the central responsibility, according to Modi, rests on the shoulders of the youths of India. Not surprisingly therefore we find the youths to be the central target audience of Modi’s Mann ki Baat.

This is further evidenced by what we call ‘the humble Prime Minister’ perspective of Modi in Mann ki Baat where he frequently downplays his own role, and instead emphasises the accomplishments of others. Modi refers to himself as ‘merely an instrument’, a sevak. The notion of being a mere tool aligns effectively with Modi's endeavours to include his audience in his political agenda. This act of belittling his own status, this faux humility of the individual who is clearly the most powerful in the nation, a person whose image is ubiquitous in public spaces, reflects a tendency among leaders worldwide to downplay their own role. Modi’s listeners would also be familiar with the feigned humility. And this humble servant image is a far cry from the muscular man Modi is presented in contexts such as election campaigns or when he claims to have provided guidance to the air force over bombing strategies in the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (POK) terrorist camps.

This humbleness of Modi, as reflected through Mann ki Baat, is also evident in his notion of nationalism, more specifically Hindu nationalism. His sense of patriotism exhibits a greater degree of inclusivity compared to the assertive Hindu nationalism that he generally represents. The Hinduness of Modi comes clearly through in the broadcasts, but it would be difficult to claim that it is a dominating theme. The term ‘Hindu’ is hardly mentioned, with only seven instances, and only in connection with names such as ‘Banaras Hindu University’ or ‘Hindustan’. This is of course only part of the picture, but the incorporation of non-Hindu festivals in his greetings and the lack of a Hindu supremacist declaration softens the image of a hard-core Hindu nationalist that is otherwise represented. This is echoed by his perhaps surprising encouragement of pride in the diversity of Indian society and his endorsement of the ‘unity in diversity’ slogan.

The underlining of the spirit of national unity is also evident in Modi’s approach to festivals. Modi almost never misses an opportunity to greet his audience on predominantly secular festivals like Diwali or Raksha bandhan, Hindu festivals with a local essence such as Ganesh Chaturthi, Durga Puja, and Onam, as well as widely observed Hindu festivals such as Saraswati puja, Holi, Chhath puja, and Kumbh mela. But he also greets on non-Hindu occasions, such as Christmas, Eid or Guru Nanak’s birthday. He does this less regularly than for Hindu festivals, but no less sincerely. Interestingly, Modi mostly uses festivals to advance a social message, including the promotion of cleanliness, the purchase of local goods and handloom items, and the promotion of environmental awareness. By doing so, he is also imbuing non-Hindu religiosity with a universal spirit.

Conclusion

Arguably there are various shades of political personae of the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as evidenced from the above discussion. In this write-up we sought to briefly analyse the image Modi presents of himself in the Mann ki Baat broadcasts. He has in other contexts presented himself in at least three different personae, but neither of those personae are present to any significant degree in his Mann ki Baat communication. Here, Modi is the elder brother who guides you, he is the uncle who indulges you but who also shares his wisdom, he is the village leader who embraces the entirety of the community, who speaks for all and represents all, who both guides and cares. He knows what is best for you and for the community, the nation, and gently implores you to take part. He does not scold, but he is firm because he knows, and he asks you to trust him.

And yet there are major contradictions between Modi's projected image and the reality of his politics in areas like caste discrimination, religious tensions, and civil rights. While an effective populist strategy, Modi's narrative omits complex realities and societal fissures. His strategic moves allow him to maintain an image of a unifying figure while sidestepping partisan politics, social atrocities and political instability and injustice. The persona Modi portrays in Mann ki Baat, exists alongside Modi as the muscular protector of the nation and the competent business-friendly leader who ensures investments and plays with the rich, or even as the ruthless promoter of a Hindu Rashtra. To explain Modi’s popularity and success at the polls, it is necessary to understand that his appeal is not that of a simple populist or a simple authoritarian. It is a complex appeal, crafted with great skill and tailored to vast and heterogeneous audiences.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the research assistants Angira Dhar, Torre Dienart, Aniruddha Mukherjee, and Poushali Chatterjee for their excellent dedication and hard work in generating and codifying the data for analysis.

Niladri Chatterjee is a historian and researcher based at the University of Oslo, Norway. His research interests include colonial and postcolonial studies, global histories, disaster politics, and South Asian history, politics, and culture. Zaad Mahmood is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science in Presidency University, Kolkata. His research interests include political economy focusing on public policy, capital-labour-interaction, work and its politics, and Indian politics. Arild Engelsen Ruud is a Professor of South Asia Studies at the University of Oslo, Norway. His research focuses on political culture in South Asia, popular perceptions of democracy, political leadership and practices.

(At The Quint, we are answerable only to our audience. Play an active role in shaping our journalism by becoming a member. Because the truth is worth it.)

1 week ago

127

1 week ago

127